Technology and medication-taking habits

Sooner or later we all end up taking medications. And we forget them. No matter how motivated or how scared of the consequences we are, forgetting is incredibly easy: the reminder doesn’t go off or we don’t have the pills when it does, we’re travelling, we’re busy, distracted, stressed… and BOOM, we missed the pill, forgot about the tablet, misplaced the inhaler.

Even though we all forget, interventions aimed at supporting patients’ memory tend to focus on chronic, life-threatening, life-changing conditions (e.g. AIDS/HIV, diabetes, cancer, hypertension) and the elderly. But young people and those on preventative treatments (such as oral contraception) forget too, even when there’s only one daily pill they have to remember. And for them remembering is often more difficult, because they don’t have symptoms, don’t have to change their whole life, and they don’t self-identify with the illness (because there’s no illness!).

Remembering medications

People tend to take their medications at the same time and in the same place every day, and if they do it for longer periods, they finally form a habit. Habits develop as we repeat actions in a stable context: the brain creates associations between the act of taking medications and the environment, present objects, preceding actions, next steps in the sequence, internal states, etc. Soon enough medication-taking turns into a habit and becomes a part of a routine, which starts to guide the behaviour.

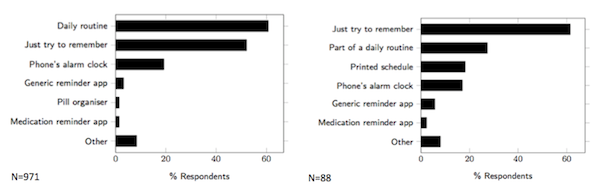

I conducted two studies that explored how people remember medications and looked at two contrasting “user” groups: women who take oral contraception (long, one pill only) and parents who have to remember their children’s antibiotics (short, strict, multiple doses per day). Among other things, I asked people how they remembered their medications and charts below summarise their responses (it was a multiple answers question; click the chart to enlarge it).

Both groups reported that daily routines were important in supporting their memory, although their role was different. For women taking oral contraception, the Pill would become a part of a routine or a routine task in itself, while parents relied on other existing routine events (getting back home, preparing meals, bedtime, etc.) as triggers. Detailed analysis of the data showed that survey respondents who reported relying on routines forgot less often than those who didn’t. The difference was statistically significant (yay!), which means that routines can’t be ignored.

What about technology?

Medication-taking is a prospective memory task, which means it is something we have to remember to do in the future. There are two types of prospective memory tasks: time-based tasks and event-based tasks. Time-based tasks are tasks that take place at a specific time or once a certain time elapses, e.g. taking medications at 9am or taking antibiotics every 8 hours. Event-based tasks are tasks that need to be completed once a certain event occurs, e.g. taking medications with your morning tea or right after waking up. Because of the connection with an existing event, event-based tasks are easier to remember: there are more contextual cues and the routine guides the behaviour. Unfortunately, most technologies ignore that and focus on giving people a reminder. They turn a habitual task into a time-based task, which is harder to remember.

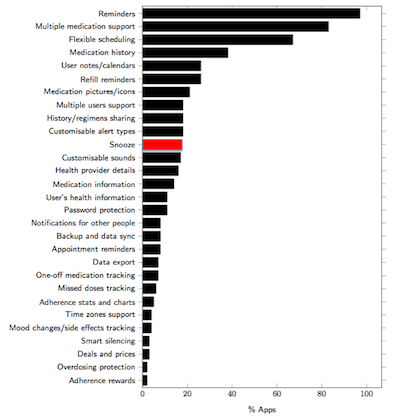

If you look at the charts above, you can see that not many research participants reported using reminders, and I am not surprised. I conducted a review of functionality offered by 229 smartphone reminder apps (106 Android and 123 iPhone apps) and the results are summarised in the chart below (click on the chart for a bigger version). Full results of that study are described in detail in my paper [pdf] and in here I wanted to point out two main problems: 1. these apps focus on reminders and time-based tasks, and ignore the fact that taking medications is a routine task; and 2. their reminders aren’t even that good – most of them don’t even have a snooze option!

Making reminder apps better

So how can we improve reminder apps? For starters, we should make sure they support daily routines. We should also listen to Maria Wolters and reduce the presence of technology.

Imagine a reminder app that suggests routine events that usually occur around the time you want to take your medications, e.g. if you want to take your pill around 8am, the app can suggest taking it after shower, after morning coffee or with breakfast. Imagine also that it doesn’t give you reminders – instead it gives you tips how to remember by yourself and a few hours later asks you if you did it. It doesn’t really remind you – it helps you create your own medication-taking habit that fits into your personal daily routine. The best part? It’s totally feasible. Smartphone apps can do it. And I’m working on such an app at the moment.

Technology is becoming ubiquitous, but maybe we don’t always need it. Maybe there shouldn’t be “an app for that”. And if there is, maybe it should just do its job, help people help themselves and then disappear, instead of teaching them that they can’t live without it.

Further reading

Stawarz, K., Cox, A. L., Blandford, A. (2014). Don’t Forget Your Pill! Designing Effective Medication Reminder Apps That Support Users’ Daily Routines. CHI’2014. [url] [pdf]

Stawarz, K., Cox, A. L., Blandford, A. (2014). Personalized routine support for tackling medication non-adherence. Personalizing Behavior Change Technologies CHI 2014 Workshop. [pdf]

Stawarz, K., Cox, A. L. (2013). How technology supporting daily habits could help women remember oral contraception. Habits in HCI Workshop, British HCI Conference. [pdf]

Maria Wolters (2014). The Minimally Effective Dose of Reminder Technology. CHI’2014 – alt.chi [url]

~Falka, 7 May 14

Powered by Textpattern. Design by Falka. 2010-2026.